A day short and a dollar late

After a rainy night in Georgia more than 40 years ago, former Atlanta Braves outfielder Gary Cooper is hopeful he’ll live long enough to see a major-league pension.

A previous version of this story first appeared at ESPN’s Andscape.com.

By Dave Mesrey

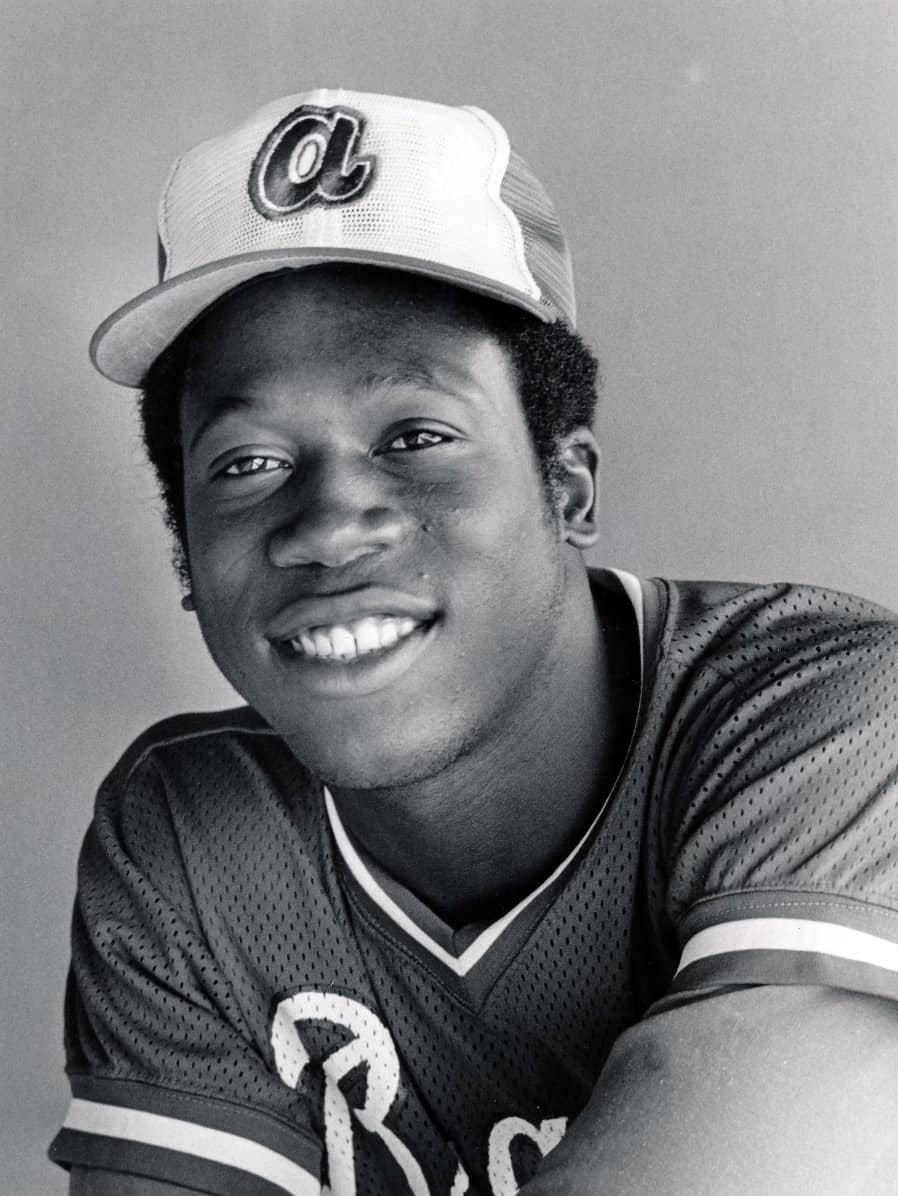

They said he was the fastest man in baseball.

In the summer of 1980, in the midst of a historic presidential campaign and the infamous Atlanta child murder mysteries, Jimmy Carter was serving his one and only term as United States president while fellow Georgian Gary Cooper was playing his one and only season of Major League Baseball.

Some of the fastest ballplayers of the era — Rickey Henderson, Ron LeFlore, and Willie Wilson — were fast becoming household names.

But for Gary Cooper, baseball held a different fate.

“If he wasn’t the fastest man in baseball,” said Paul Snyder, longtime scouting director for the Atlanta Braves, “he was right up there with the next guy.”

Cooper, then a 23-year-old rookie outfielder, spent 42 days on the Braves roster that summer as a pinch-runner and late-inning defensive specialist for manager Bobby Cox.

But just a week after a rainout against the San Francisco Giants on Sept. 28 that year — a game the Braves were not required to make up — Cooper was sent back to the minor leagues and never made it back to the show.

In his final appearance in a major-league uniform, on Oct. 5, 1980, Cooper was standing in the on-deck circle at Cincinnati’s Riverfront Stadium when Reds reliever Tom Hume struck out Braves slugger Dale Murphy to end the game and end the season.

After one more year in the Braves farm system, with the 1981 Durham Bulls, Cooper decided to hang up his spikes.

“I didn’t have nothin’ to prove back in the minors,” he says. “I just felt like it was time to call it quits.”

But what Cooper didn’t fully realize until many years later is that he’d come within 24 hours — just one day on the Braves roster — of qualifying for a pension from the Major League Baseball Players Association.

The MLBPA, according to Society for American Baseball Research Scouts Committee chairman Rod Nelson, is “the most successful and well-endowed labor union in the history of mankind.” As of its latest filing in 2021, the MLB Players Benefit Plan had 9,847 participants and over $4.5 billion in assets. But since 1980, the union’s minimum amount of major-league service time needed to qualify for a pension has been 43 days.

“It’s a game of inches,” says Steve Butts of the Institute for Baseball Studies. “But when we’re talking about millionaires and billionaires, the rank and file get lost in the shuffle.”

Back in Cooper’s era, Black players who were regarded as marginal prospects would only get one chance in the show, says Gary Gillette, former editor of the ESPN Baseball Encyclopedia and founder and chairman of the Friends of Historic Hamtramck Stadium.

“And if they didn’t perform well,” Gillette adds, “they would be sent back to the minors and often never got a second shot to prove themselves.”

“We just eat, shit, and played baseball”

Cooper first discovered baseball through his father, Nathaniel, who in the 1950s made a name for himself as a shortstop on the sandlots of Savannah.

“My daddy should’ve been in the majors,” Cooper says. “He was awesome. That’s all our family did — we just eat, shit, and played baseball.”

As a three-sport star at Groves High School in nearby Garden City, Georgia, Cooper also excelled at football and track and once ran the 100-yard dash in 9.7 seconds. As a starting pitcher for Groves, he went 19-3 and threw three no-hitters. At the plate his senior year, he batted .454.

Cooper was selected by Atlanta in the third round of the 1975 MLB draft and spent seven years in the Braves organization, racking up 213 stolen bases along the way. And before he got called up to the majors, he played three seasons with the AA Savannah Braves, whose home games took place at Grayson Stadium, now home of the world-famous Savannah Bananas.

At the time, the Braves’ vice president and director of player personnel was Bill Lucas, the first Black man to run a Major League Baseball team.

“Luke was like a father figure to me,” Cooper says. “When he passed [away], it was a huge loss for the Braves.”

Cooper spent much of his time in the minors playing alongside catcher Brian Snitker, who’s been the Braves manager since 2016 and led the team to a World Series title in 2021. But while Cooper got a taste of the big time back in the day, Snitker never made it past AAA.

Hammer time

In August of 1980, Cooper and the Savannah Braves were in Florida for a game against the AA Jacksonville Suns when his manager, Eddie Haas, took him aside.

Haas had just gotten off the phone with Braves vice president of player development Hank Aaron, who’d called to say the Braves needed Cooper’s speed in the big leagues. Aaron wanted Cooper to meet the big club in Pittsburgh, where Bobby Cox’s squad was scheduled to take on Dave Parker and the defending world champion Pittsburgh Pirates at historic Three Rivers Stadium.

“I thought Eddie was playin’ with me,” Cooper recalls. “I asked him, ‘Man, why you took me out the lineup?’

It was a big surprise, he told the Atlanta Constitution that day. “I started sweating the minute they told me.”

“I’d never even been to Pittsburgh before,” Cooper says. “I was so excited, I walked into the wrong locker room!”

With the Braves leading 8-4 in the bottom of the seventh, Cox inserted Cooper into left field for his defense amid the giant expanse of Tartan Turf at Three Rivers Stadium.

In the bottom of the ninth with the Braves up 8-5, Pirates speedster Omar Moreno stepped to the plate with two out and a runner on second. Moreno promptly laced a single to left off Braves reliever Larry Bradford. Pirates pinch-hitter Mike Easler dashed home from second to cut the Braves’ lead to 8-6, but then Moreno got caught trying to stretch a single into a double.

“Omar lined one to me in left and it bounced over my head,” Cooper says. “But I turned around and snagged it and threw him out at second base — and that ended the game.

“That was one of my biggest thrills in the major leagues,” he says. “It was just like hitting a home run to win the game.”

What is an MLB pension worth?

According to Phoenix-based Athlete Wealth Management, an MLB player can earn a partial pension for each quarter (43 days) of service time, which in 2021 was valued at $5,750.

“I have no idea what that valuation is all about,” says former Montreal Expos pitcher Steve Rogers, who now serves as Special Assistant of Player Benefits with the MLBPA.

“Benefits are paid monthly,” he says, “but there’s no present value — we don’t deal in that. You can make some assumptions, but there’s no lump-sum value.”

So even if Cooper qualified for the bare minimum, it’s not clear what his pension would be worth or what it would cost the MLBPA.

“There’s a relatively small group of these players” who don’t receive a pension, Butts says. “A net cost could hypothetically be calculated to show that it would be a thimbleful of money compared to one of the league’s streaming deals.”

Few major leaguers actually accumulate enough savings or pensions to retire comfortably.

Because Cooper made his major-league debut in 1980 after MLB’s new collective-bargaining agreement took effect, he needed only 43 days on the Braves’ roster to qualify for a pension. And while he’s unique in that he’s just one day shy of qualifying, he’s not the only former major leaguer struggling to secure his retirement. One such player is former Detroit Tiger Les Cain, who’s been fighting to obtain a pension for years.

According to researcher Max Effgen, of BitterCupBaseball.com, there are more than 500 former major-league players who played before 1980 who receive a non-qualified retirement benefit that pays up to $11,500 a year.

Of those players, says Bitter Cup of Coffee author Doug Gladstone, “There are 176 poor, unfortunate souls who don’t get anything because they had less than 43 days of service credit.”

And then there’s former Houston Astro Aaron Pointer, who receives an annual pension of about $900.

Had Cooper been given a longer look in the big leagues, Gillette believes his ability to draw walks and get on base could’ve helped his chances. Back then, however, it was almost completely ignored.

“When the Moneyball analytics revolution came along two decades later,” Gillette adds, “the perceived value of getting on-base skyrocketed, and a progressive team like Oakland might have given another chance to a speedburner like Cooper who walked a lot, but not in the 1970s and 1980s.”

Cooper’s Detroit-based attorney, Kevin Campbell, recently requested an exemption for Cooper from MLB’s 43-day minimum amount of service time to qualify for a pension. But in its response to Campbell, the Major League Players Benefit Plan denied Cooper’s request for a pension and health benefits.

“The Pension Committee appreciates Mr. Cooper’s difficult circumstances,” its rejection letter reads, “but is unable to grant him benefits under the Plan.”

Coop’s troops

Even if Cooper’s 1980 Braves had made up their rainout from Sept. 28 that year, the MLBPA’s Rogers says the union still would not have counted that as service time for Cooper. But, he adds, former players like Cooper can earn service time as a major-league coach.

To that end, Savannah businessman Robert Jonas has launched a petition urging the Atlanta Braves to add Cooper to their coaching staff for just one game of the 2024 season.

“I’ve known Gary for about 11 years now,” Jonas says. “He’s so down to earth — you’d never know in a million years, as humble as he is, that he actually played for the Braves. Over the years, his path hasn’t been the easiest, but he just keeps on truckin’. When life gives him lemons, he finds a way to make lemonade.”

Currently, the Braves do not have a baserunning coach listed on their staff. And no one on the team’s 40-man roster has been assigned Cooper’s old jersey number, 22.

Snitker, perhaps fittingly, wears No. 43.

In 1968, when legendary former Negro Leagues pitcher Satchel Paige needed just 158 days on an active major-league roster to reach the five-year minimum required to receive a pension, 19 teams turned him down.

But one club stepped up and signed the 62-year-old former star as a part-time pitcher and special team adviser: the Atlanta Braves.

Although he never played a regular-season game for the Braves, Satch eventually got his pension.

“The Braves could do Coop like they did Satchel Paige,” says former Detroit Tiger Ike Blessitt. “If they just add him to their [coaching] staff for a day — maybe then the man can finally get his pension.”

Today, Cooper, 67, lives a spartan lifestyle in his hometown of Savannah. In recent years, he has struggled with homelessness, but today he is a proud senior citizen. Last spring, Cooper was even inducted into the Greater Savannah Athletic Hall of Fame.

Today he works part-time as a landscaper, but lately work has been scarce. Cooper has no car, no home to call his own, no savings, no pension, and struggles just to pay his phone bill every month.

That’s why Jonas is swinging for the fences. In the event he strikes out on his petition drive, he’s also launched a crowdfunding campaign to help support Cooper.

“Whatever I can do to help Gary,” Jonas says. “It’s been a rough ride for him these last few years, so hopefully this petition and the GoFundMe will help the cause.”

“I think most of us, as humans, can identify with being, at one point or another, a day late or a dollar short,” Campbell says. “But Gary’s case is unique … because he came up short through no fault of his own, under rather freakish circumstances.”

So what would Cooper do if the Braves actually reached out to him?

“Man, I wouldn’t know how to react,” he says.

But Blessitt, the former Tiger, sees a light at the end of the tunnel for players like Cooper and himself.

“If we all work together with Major League Baseball, I know we can fix this,” he says. “It might not be the easy thing, but it’s the right thing.”